Roots of Cool 4: Authentic Expression and the Birth of Jazz

Part 4: How music, authenticity, and forbidden pleasures brought cultures and art forms together.

NOTE: After publishing this series, I stopped using “coolness” to describe this vibe. I now refer to it as the Natural Vibe. The research and analysis still apply.

In the era after slavery, the notions of coolness and hipness fused with a spirit of rebellion in a diverse melting pot of culture and creativity.

As formerly enslaved people settled in the American South, these qualities came with them and were often expressed through music. Talented African Americans found outlets for authentic expression related to their experience of oppression and segregation.

This fusion of people, culture, music, religion, and emotion created the early manifestations of an art form that would come to define “cool” around the world: American music.

Let’s take a tour of the music and the people who made it happen.

Minstrel Shows

One of the early forms of entertainment was traveling shows that often featured white actors in blackface performing skits based on stereotypes and tropes of Black culture. The shows, mostly in the 1800s, were most popular in the north and midwest of America, where there was limited experience with African Americans.

These racist portrayals misrepresented Black culture and led to many of the reductive and damaging stereotypes that remain today. Nevertheless, they were popular at the time and represented one of the first times White actors and audiences engaged with Black culture.

Black Church Gospels

During the era of minstrel shows, African American culture and music continued to develop, often in places that reflected segregation.

From the 1700s onward, many Africans converted to Christianity as part of the Great Awakening. In America, White churches became segregated, leaving no place for Black people to worship. The first Black churches in America were established in the late 1700s to fill this gap. These churches birthed an important American art form: gospel music.

Rev. Al Sharpton in the excellent documentary Summer of Soul:

Gospel was more than religious, gospel was the therapy for the stress and pressure of being Black in America. We didn’t go to a psychiatrist, we didn’t lay on a couch, but we knew Mahalia Jackson.

🎥 Watch Ms. Jackson perform Lord Don’t Move the Mountain

Greg Tate in the Summer of Soul:

There was something happening in Black America where the only place we could be expressive was in music, was in these church rituals. Gospel was channeling the emotional core of black people. And that probably goes back to the first moments of the black conversion to Christianity

There is this notion of spirit possession that comes from Africa, that's part of seeking some kind of release, some kind of catharsis.

Black churches became places for authentic expression and emotion that couldn’t be shared elsewhere.

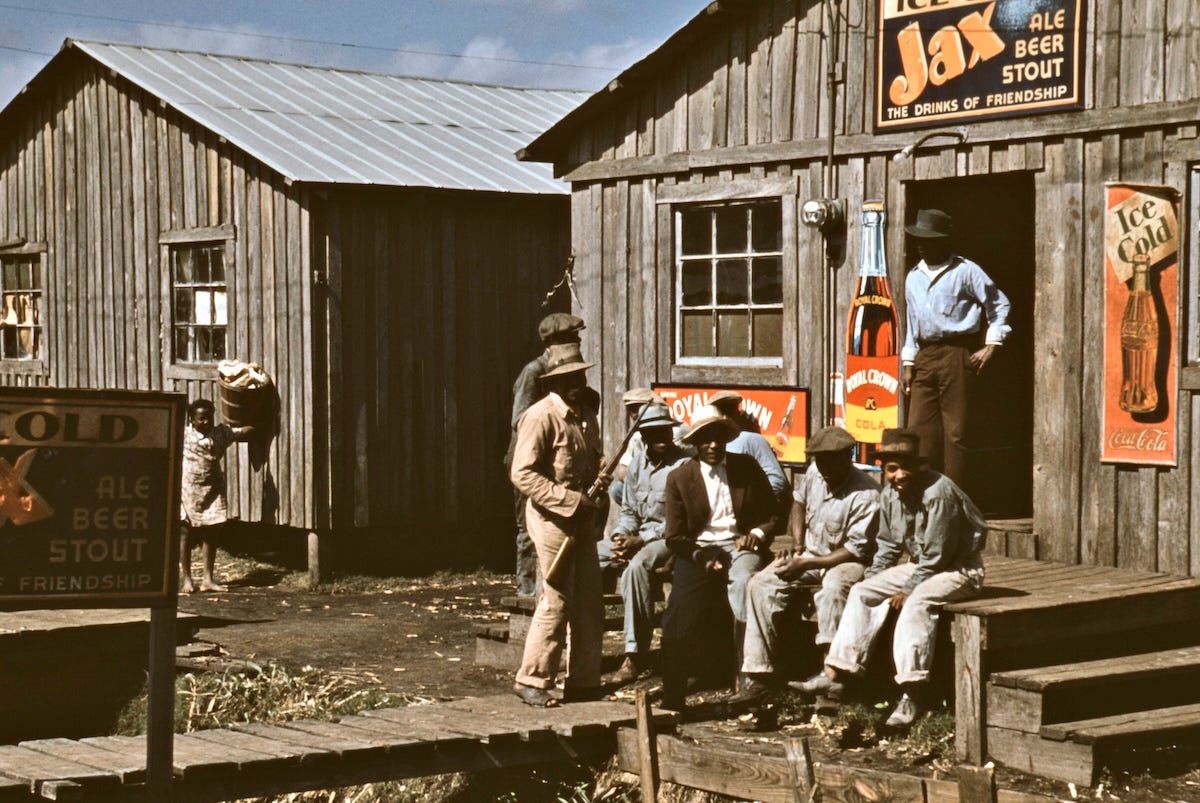

Juke Joints

The juke joint is one of the crucibles of American music. In the early days of the blues, artists like Robert Johnson, Ma Rainey, and Muddy Waters played juke joints throughout the South. The music evolved from African spirituals and work songs adapted to express the struggles and joys of everyday life. The songs were soulful and cathartic and only required basic instruments: a guitar, harmonica, and DIY instruments like a washboard.

🔊 Listen to Ma Rainey sing “Jealous Hearted Blues” in 1924.

Juke joints were also places of forbidden pleasure—gambling, drinking, and dancing. While the music was essential, these establishments symbolized resistance and a way to feel free in a segregated society. They were places for rebels, snappy dressers, and people who could keep their cool.

The term "juke" is believed to come from the Wolof word “dzug”, which means to misconduct oneself.

As Black musicians traveled from juke joints to cities in the South and Midwest, they were exposed to new instruments and musical forms. In New Orleans, for example, they adopted brass instruments like the trumpet and reed instruments like the saxophone. Starting in the 1930s, the Chitlin Circuit helped Black musicians find work in Black-owned establishments.

This experience, combined with the emotions and catharsis of gospel music, set the stage for more innovation.

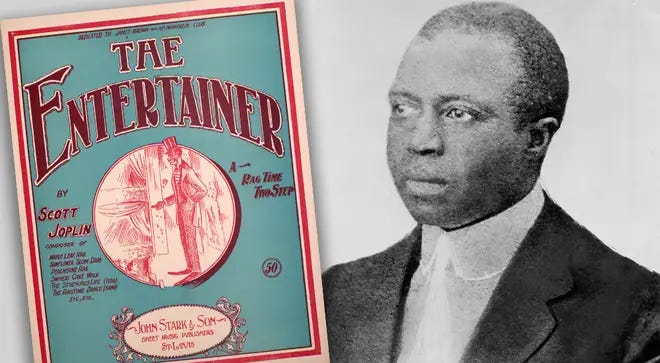

Ragtime

Ragtime gained popularity in the 1800s and early 1900s. Unlike blues music, which has a rougher sound, ragtime is upbeat and lighthearted. Artists like Scott Joplin built on the positive emotions and prosperity of the post-WWI era.

🔊 Listen to Scott Joplin’s first hit: Maple Leaf Rag

Fusion and the Birth of Jazz

Over time, the rhythms, emotions, and improvisation of the blues and gospel were mixed with new instruments from the cities and inspirations from ragtime. Together, these helped create the era of “big band” or “swing” music, which had rhythms and styles perfect for dancing the jitterbug and the Charleston. Our friend Cab Calloway and the Cotton Club were famous at the time.

This combination of influences, mostly based on African American musicians, birthed one of the most influential musical forms in American history and the roots of cool: jazz.

As we’ll see, jazz music and musicians became a symbol of coolness, hipness, rebellion, and authentic expression in the 20th century.

Cultural Integration and Rebellion

This new environment was becoming more integrated, even in the face of systemic racism and segregation.

This was the Roaring 20s and the era of flappers—mostly White women who took pride in flouting social and sexual norms. They drank alcohol and smoked. They wore short skirts, bobbed hair, and excessive make-up. They were the rebels of their time who were celebrating suffrage and the end of WWI.

At the time, American White culture was mostly conservative, modest, and focused on strict moral codes. The emergence of flappers, jazz, and dance halls threatened these ideals and they fought back. This set up a dynamic we’ll see repeatedly: those who seek to uphold traditional standards versus those who rebel against them.

This rebelliousness pushed the limits of segregation. For Flappers and others, dance halls were places of freedom and expression. In addition to drinking and dancing, they were drawn to the authenticity and emotional depth of African American artistry. While inequity was still very real, White audiences began to accept and respect Black musicians.

The Roaring 20s was also a time when White people began to express a new kind of authenticity, choosing to be themselves rather than the person society expected them to be. This break from tradition was a rebellion against social norms that would kickstart more rebellion in the future.

Prohibition and Speakeasies

One of the great bummers of US history, the Volstead Act of 1920, made alcohol illegal. This created a predictable side effect: the growing popularity of underground bars and clubs called speakeasies. These forbidden establishments, like juke joints, operated outside the law and provided a place for debauchery and all-night parties fueled by high-energy swing and jazz.

Like dance halls, speakeasies provided more opportunities for racial and cultural integration. The availability of booze and good times brought together musicians, rebels, and tastemakers of all cultures. Black musicians fused African rhythms with contemporary American music to create new forms of jazz that became the era's defining soundtrack.

This cross-pollination of coolness would define popular culture in the 20th century. White people felt inspired by Black culture and engaged with it like never before. Jazz and jazz musicians added authentic and artful elements to American culture, as dance halls and speakeasies provided opportunities for integration instead of segregation.

The people… Black, White, or otherwise, who were part of this scene witnessed the birth of American cool that reflects African traditions, generations of hardship and oppression, authentic expression, and a healthy dose of rebellion.

Amid this new, exciting environment, a new dynamic was emerging: White artists were able to use their structural advantage to copy and profit from African American culture and music. This dynamic will be an important part of this story going forward.

A Test

A goal of this series is to define specific qualities that anyone with a “cool” vibe exhibits. We can test these qualities with a simple question:

Is a “cool” vibe possible without expressions of authenticity?

Coming Up…

We’ll finish this series by examining jazz's continuing role in the popularity of radio, commerce, and the emergence of a new counterculture.

👉 Read a summary of The Natural Vibe.

Amazing stuff Lee. I can imagine that this wasn’t easy and may have come with some uneasiness toward writing about and sharing your work on some of these topics with the world. I commend you for all the hard work and thoughtfulness that clearly went into this.