Roots of Cool 3: Rebellion, Revolution, and Fusion

Part 3: How enslaved people brought "cool" and "hip" to the New World

NOTE: After publishing this series, I stopped using “coolness” to describe this vibe. I now refer to it as the Natural Vibe. The research and analysis still apply.

Up to now, we’ve looked at the origins of American cool via West Africa.

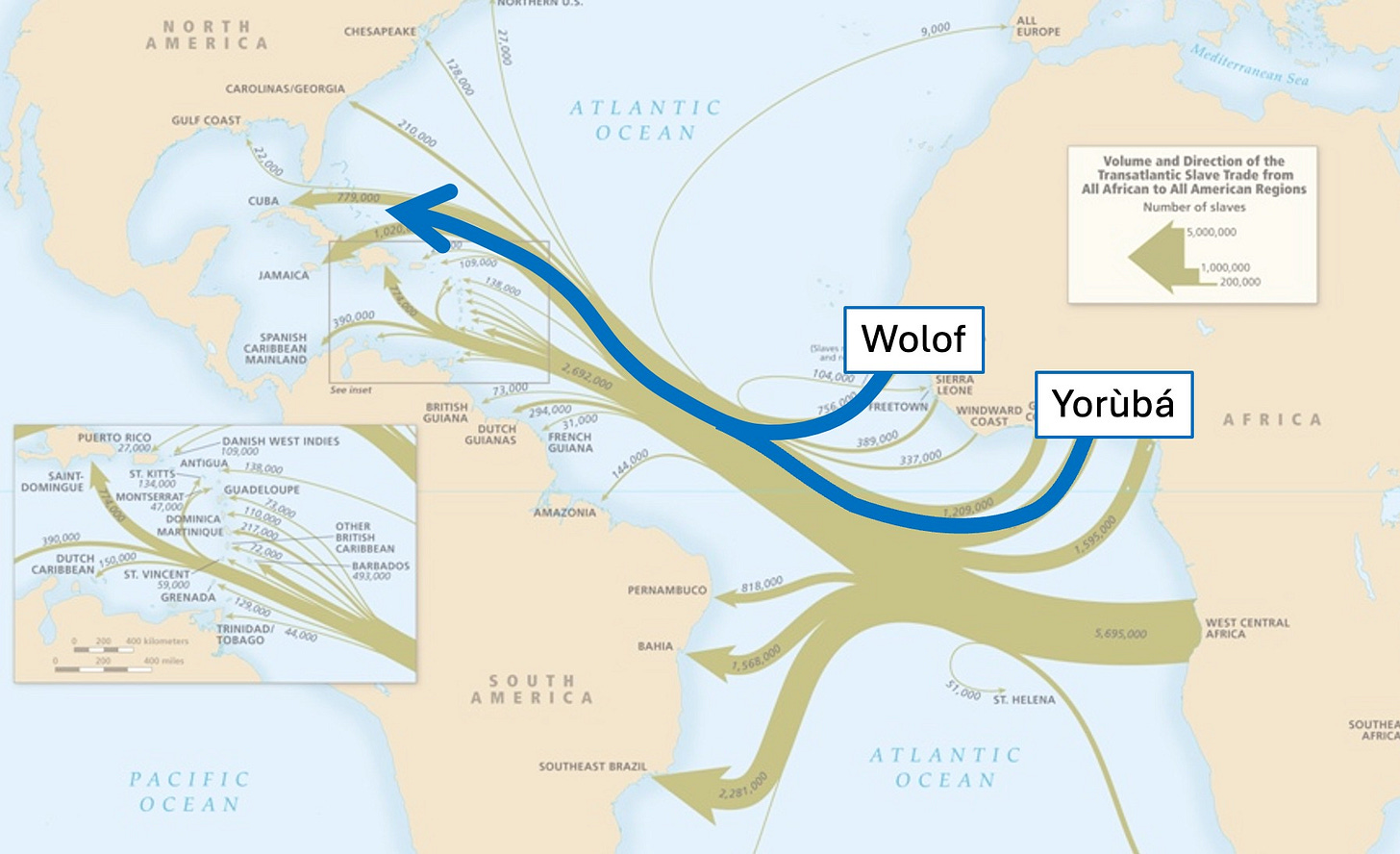

From the Yorùbá, we learned about itutu, which refers to coolness and composure.

From the Wolof, we learned about the hipi, which is the likely origin of the modern word “hip” and refers to cultural and social awareness.

Composure and awareness. These are words to remember in this series.

As we’ll see below, the atrocities of slavery had side effects that relate to the evolution of coolness and the development of African American culture.

West Africans in the New World

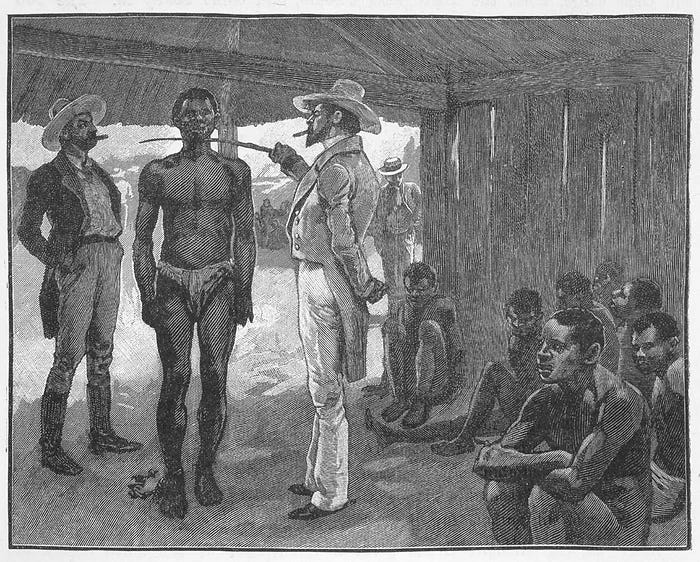

Imagine it’s the 1500s, and you’re in West Africa. Slavery is a part of society, but it’s mostly based on the captured enemies of rival kingdoms. It’s terrifying, but happens among familiar cultures and languages, and release is possible.

Then, everything changes. Europeans arrive and start enslaving your people with the help of local slave traders. Soon enough, they demand that your family board a ship to the New World or be killed. Your family, your culture, your religion, and your sense of self all seem to vanish.

How must it have felt to live through this? I can’t fathom it.

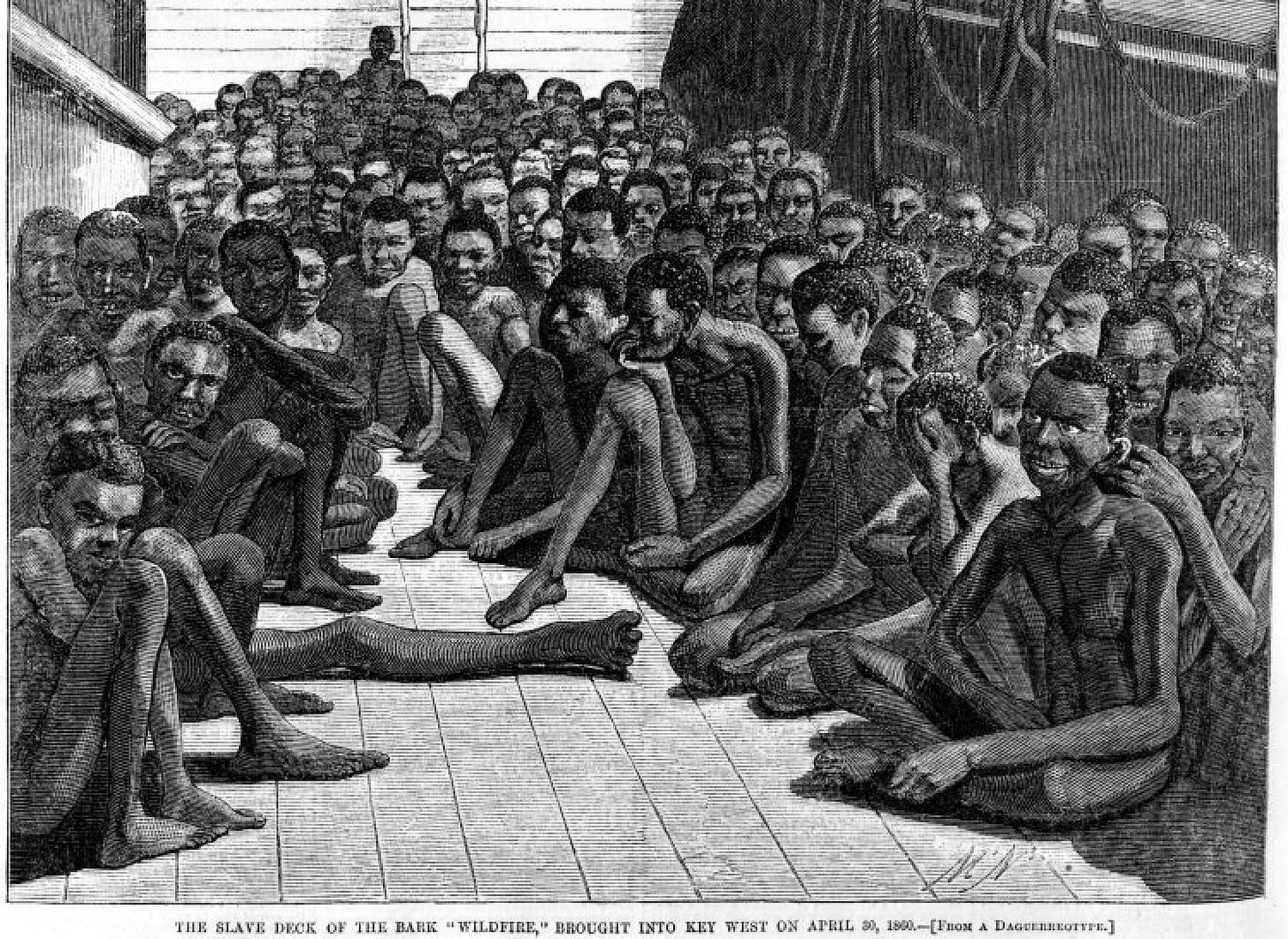

The illustration below is captioned “From a Daguerreotype,” which means the original was captured with an early camera.

Africans like the Wolof and Yorùbá had no choice. They had to find ways to maintain their dignity and respect in the face of slavery. This took many forms, but specific qualities of both Yorùbá and Wolof cultures became part of the melting pot of the New World, and eventually America.

The Yorùbá: Cool in the Face of Oppression

Let’s fast forward to the late 1700s and early 1800s. The Yorùbá arrived in the New World and faced the same oppression and brutality as other Africans.

Frederick Douglass wrote about his experience.

I have often been awakened at the dawn of day by the most heart-rending shrieks of an own aunt of mine, whom he used to tie up to a joist, and whip upon her naked back till she was literally covered with blood … The louder she screamed, the harder he whipped; and where the blood ran fastest, there he whipped longest.

Cruelty and violence were part of life for many. Severe punishment could be meted out for the smallest transgressions. Enslaved people who lost their composure, acted out, or fought against owners could risk brutal punishment or even death.

The Yorùbá had a secret weapon: itutu. This is the Yorùbá concept of composure, emotional restraint, and grace under pressure.

The Yorùbá used itutu as an act of resistance. By staying calm and collected in the face of oppression, they preserved their dignity and denied their oppressors the satisfaction of seeing them break.

Emem Michael Udo, a Yoruba scholar at the University of Oyo, writes

The strength of Yoruba culture was, therefore, most tested in the fields of the plantations and in slaves’ ability to maintain the contours of their cultural personality in foreign lands, essentially negotiating their Africanness under the noses of slave masters and European institutions.

Ernest Hemingway’s definition of bravery as “grace under pressure” is apt. It took bravery and willpower to remain composed in these conditions. Like hipi, this quality was respected and influential among the enslaved.

The Wolof: Rebels from the Start

In part two we covered the Wolof concept of “hipi”. Now we’ll add another layer to Wolof culture: rebellion.

The Wolof had the terrible misfortune of living near ports closest to the New World, which made it easier for them to be enslaved. This was a clear violation of their cultural identity and Muslim religion. They did not submit easily.

The First Revolt

Diego, the son of Christopher freakin’ Columbus, owned a plantation in what is now the Dominican Republic. On his plantation, the Wolof led the first recorded slave revolt in the Americas, in 1522.

From The Servants of Allah, by Sylviane A. Diouf

Wolof Muslims “went from plantation to plantation trying to rally other Africans” because “they could not accept being enslaved by Christians or forced to convert. Their complete refusal of their new situation translated into disobedience and rebellions”

This legacy of rebellion stayed with the Wolof name but was not unique to them. Most Africans in the New World had valid reasons to resist, instilling a spirit of rebellion that was passed through generations.

Wolof Language

Because the Wolof were among the first to be enslaved, their language became a part of the culture in the New World.

During the colonial period, planters had little trouble finding Wolof speakers to translate for newly arrived Africans from the region. Thus, Wolof was the first African language to reach the American plantations and lay a linguistic foundation on which other African languages would follow.

This is likely how the Wolof word “hipi”, meaning awareness, eventually made it to America and became “hip”, “hipster”, “hippy”, and “hip-hop”.

The Melting Pot Diversifies

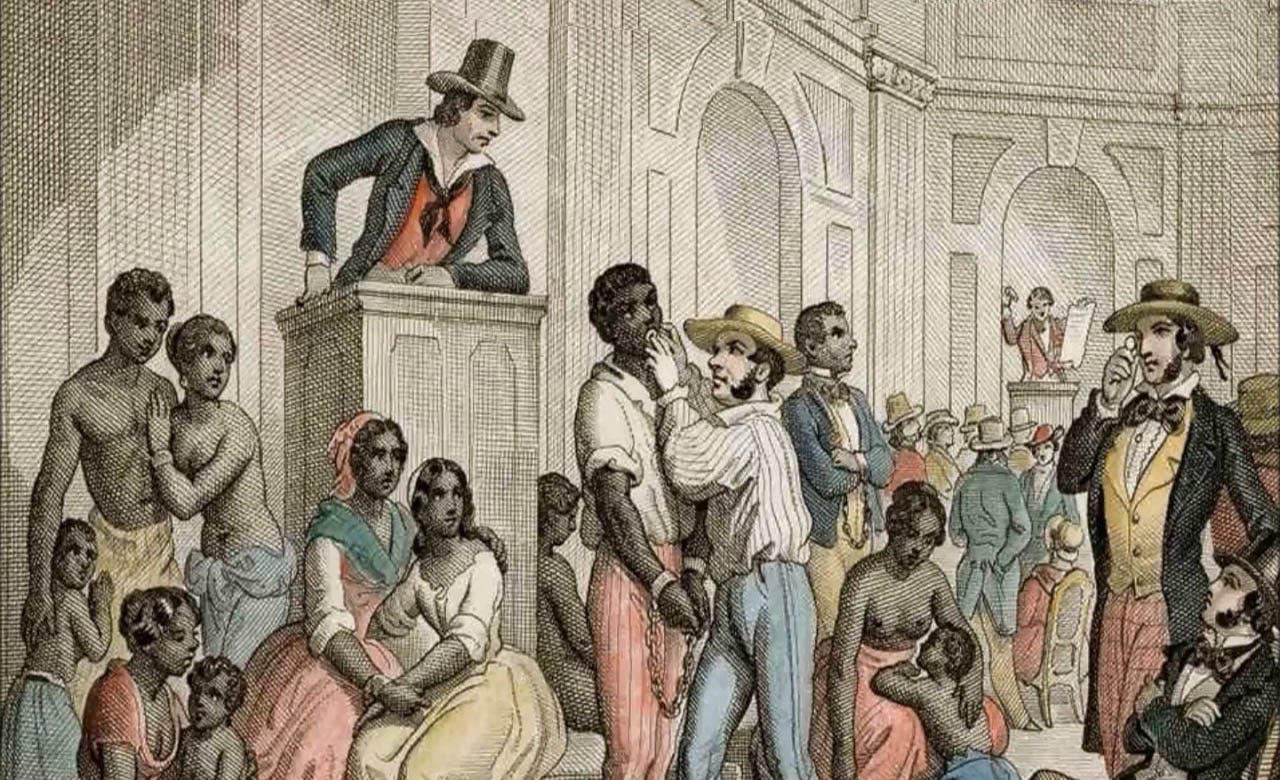

During slavery, the Caribbean was one of the most diverse places on earth. English, French, Spanish, and early American colonists mixed with many African cultures and indigenous people. As they lived and worked together for generations in places like Haiti and Cuba, cultural integration was inevitable.

Enslaved people learned European and indigenous languages, customs, music, and cultures that mixed with their own. West Africa's griot tradition helped ensure that stories and music remained. This cross-pollination created new forms of religion, music, and art that eventually became part of African American culture.

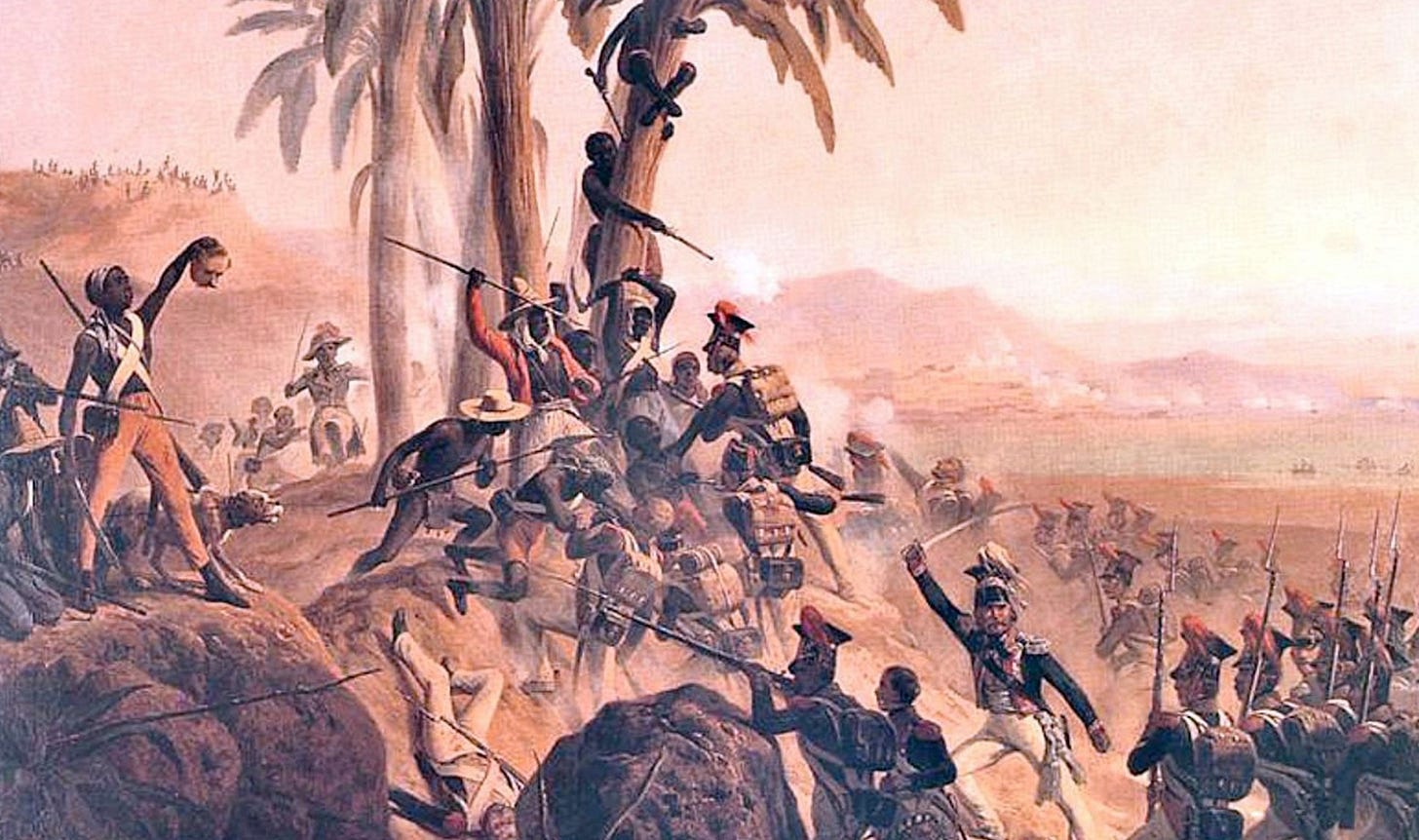

The Haitian Revolution and the End of Slavery

In the 1700s, Haiti was a French colony built on the labor of enslaved Africans, mostly on sugar plantations. Over generations, they reached a breaking point.

Starting in 1791, enslaved people (and free people of color) organized one of the most incredible revolutions in history, led by the son of two slaves: Toussaint Louverture. By 1804, Haitians defeated Napoleon’s army in Haiti and became the first independent Black republic and the first nation in the West to abolish slavery.

This was a pivotal moment in African American history. Frederick Douglass in 1893:

“We should not forget that the freedom you and I enjoy today is largely due to the brave stand taken by the black sons of Haiti ninety years ago…striking for freedom, they struck for the freedom of every black man in the world.”

The Haitian Revolution (1791) occurred within years of the French (1789) and American (1775) revolutions.

Rebellion was in the air just as America was being born.

The Caribbean to New Orleans

Sugar cane paved the path from the Caribbean to the American South. Plantation trade routes connected Haiti and Cuba to New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta, where many free Black families reconnected and settled.

Free Blacks in America represented a unique mix of culture and experience that formed over many generations. They retained stories, rhythms, and traditions rooted in Africa. They learned instruments, languages, and customs from Europe and the Caribbean. They practiced and appreciated the qualities of cool composure and cultural awareness of their homelands. They felt the spirit of rebellion that came from their fight against oppression.

These are primordial elements of coolness in America.

A Quick Test

A goal of this series is to define specific qualities that anyone with a “cool” vibe exhibits. We can test these qualities with a simple question:

Is a “cool” vibe possible without a spirit of rebellion?

Coming Up…

Next, we’ll focus on an essential element of coolness that grew out of the passion and creativity of Black communities in the American South. This element is based on the cultural DNA of survival, resilience, rebellion, and self-expression.

👉 Read a summary of The Natural Vibe.

Keep these coming! Excellent research you’re doing is fascinating while also being a reminder of America’s past.